We will not teach anyone what a pineapple is, but it is interesting to say a few words about this fruit that seems so familiar that we no longer see its strange appearance. Indeed, when the first Europeans discovered it in Brazil in the 16th century, they had a lot of trouble describing it. Here is the “sketch” that Jean de Léry made in 1578, with reference to the plants of the “old continent”: “The plant that produces the fruit named by the savages Nanas is similar in shape to gladioli and still having the leaves a little curved and fluted so much around, more approaching those of aloe. It also grows not only clustered like a large thistle, but also its fruit which is the size of a medium-sized melon and shaped like a pine cone, without hanging or leaning to one side or the other, comes from the same kind of our artichokes.”

You notice that Jean de Léry, who could be said to be the first of the ethnologists, retained the name given by the “savages”, and it is this name which will be taken over by science and by most languages such as Lao, Cambodian or French; Others like English or Spanish will see in this fruit a resemblance to the pine cone; we have not been able to decipher the meaning of the Thai name sapparot, but, thanks to Jacques Lemoine, we know that the name Hmong tsiv puv luj, is a loan from the Chinese language and not from the Thai language as some people think.

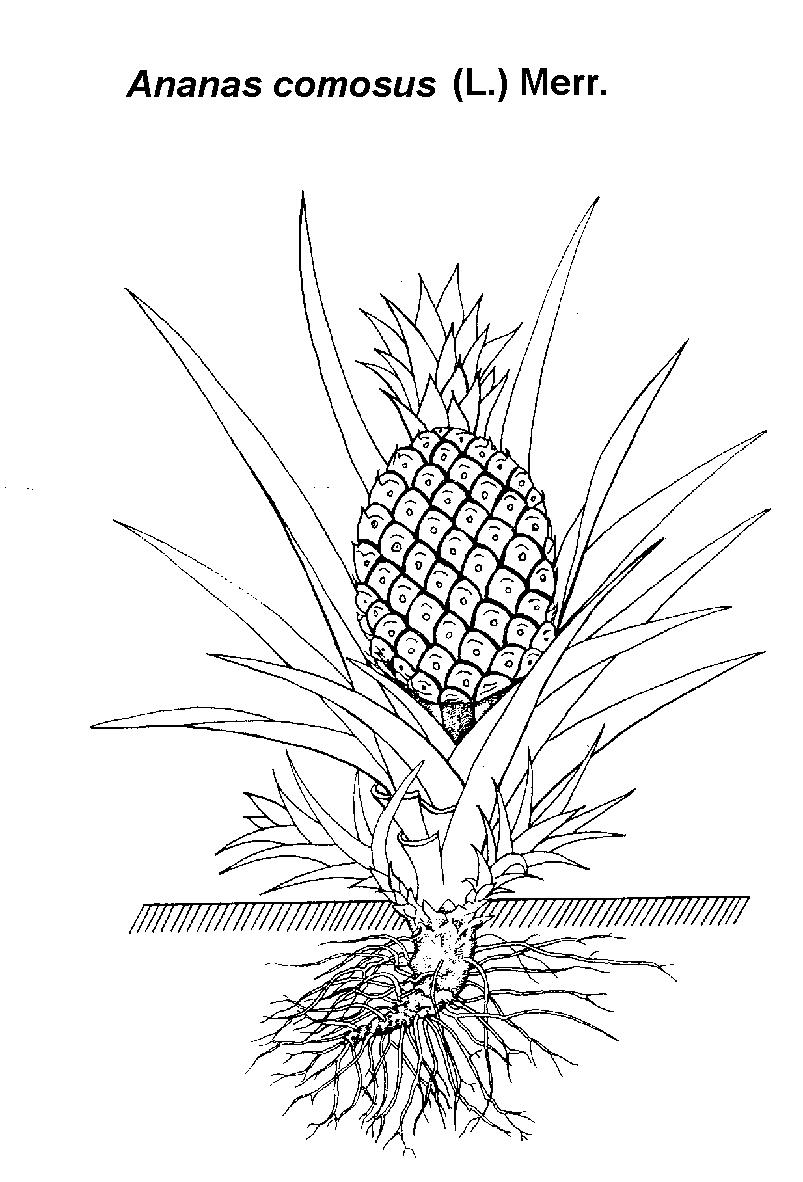

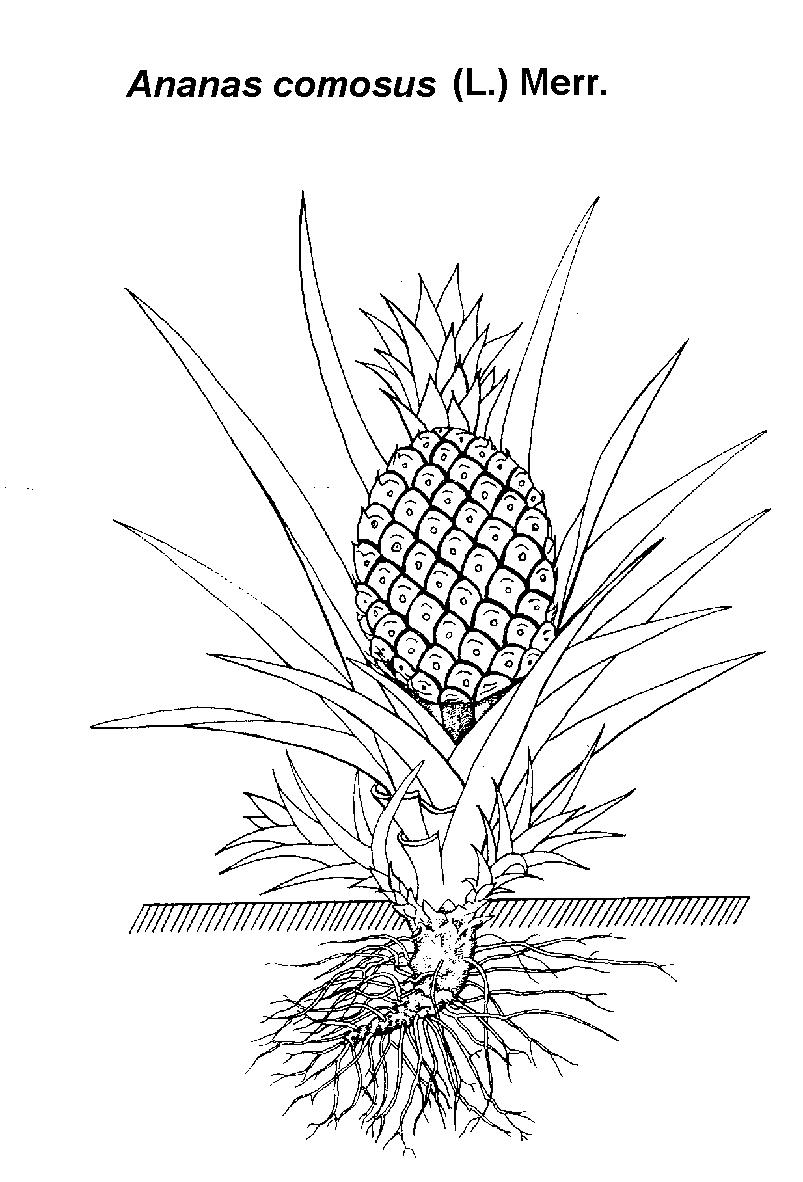

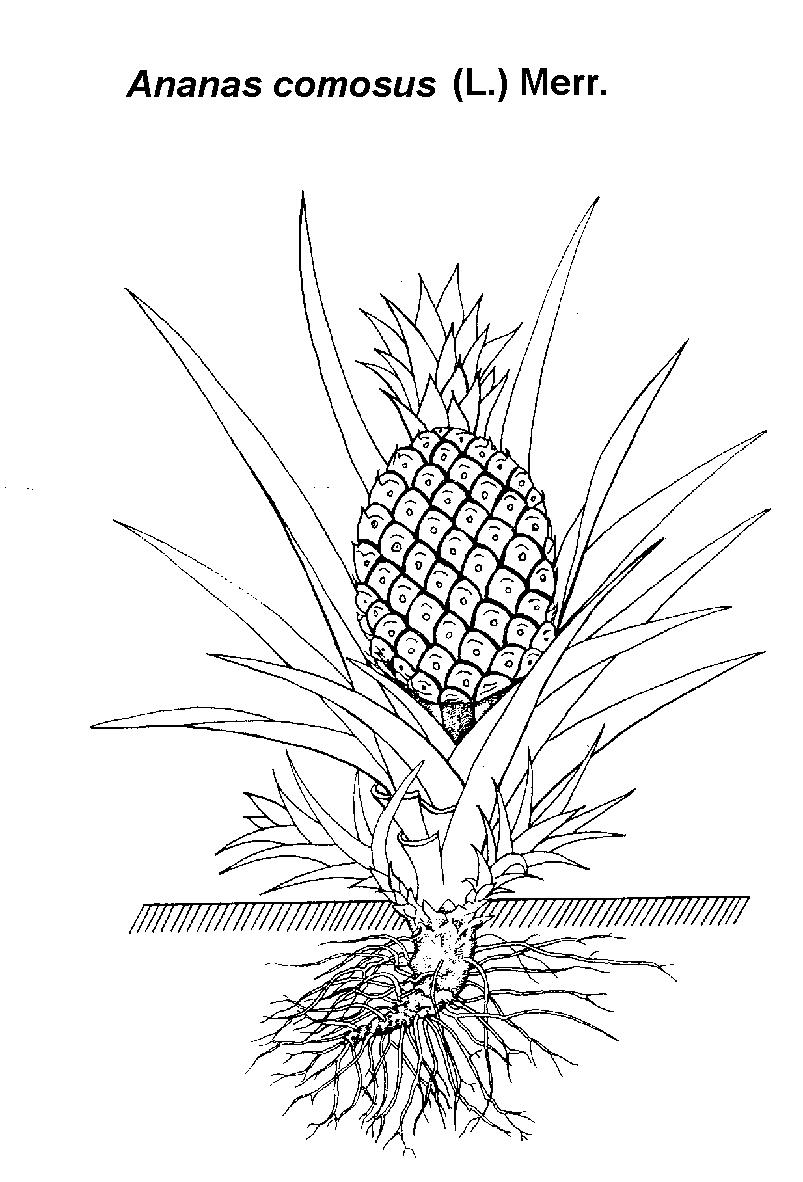

The pineapple belongs to the Bromeliaceae family (from Bromel, a Swedish physician of the 17th century) which is made up of plants that are almost all epiphytes and almost all American. However, mak nat is not epiphytic: it is a terrestrial species of herbaceous plant which can reach 1m to 1,50m with long lanceolate leaves from 50cm to 1,80m, toothed in general, but sometimes smooth. The flowering of the pineapple is characteristic of the Bromeliaceae, with at the end of a generally single stem a crown of short leaves above a set of small flowers giving numerous conical fruits, which grow individually until they join, forming at maturity the large “fruit” that we know. The rind is composed of hexagonal patterns and the flesh is very juicy and varies in color depending on the cultivar.

The pineapple was introduced in 1518 by the Portuguese in India, it then spread in Asia where each region has long developed particular uses of this plant. In Laos the traditional uses of mak nat are numerous. The fruit is of course eaten fresh, but it is also the ingredient of some cooked dishes: while still green, it is used in soups to make them more acidic; when ripe, it is the sweet note in many “sweet and sour” preparations; the young shoots are used in curries in the manner of bamboo shoots; the peels of the fruit are added to padèk to hasten its fermentation and to give it more flavor. In the past, a thread for sewing was extracted from the leaves, but this was at the expense of the fruit. The medicinal uses of mak nat are mainly for digestive problems, as it is a diuretic confirmed by chemical analysis; it also has the reputation of being antifebrile and even abortifacient (leaves, green fruits).

Although it has been introduced for a very long time in gardens, pineapple has recently been extensively exploited in Laos to be sold to the food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries (pineapple would make you lose weight!). Pineapple juice and jams are well known here and are part of the fair trade circuit. With a production of 32 000 tons per year, this fruit allows many small farmers to improve their standard of living by providing them with a job and a fixed income.

Nous n’apprendrons à personne ce qu’est un ananas, il est cependant intéressant de dire quelques mots de ce fruit qui nous parait familier au point que l’on n’en voit plus l’aspect étrange. En effet, lorsque les premiers Européens l’ont découvert au Brésil au XVI° siècle, ils ont eu beaucoup de difficultés à le décrire. Voici le « portrait-robot » qu’en fait Jean de Léry en 1578, par référence aux plantes du « vieux continent »: « La plante qui produit le fruit nommé par les sauvages nanas est de figure semblable aux glaïeuls et encore ayant les feuilles un peu courbées et cannelées tant à l’entour, plus approchantes de celles d’aloès. Elle croît aussi non seulement amoncelée comme un grand chardon, mais aussi son fruit qui est de la grosseur d’un moyen melon et de façon comme une pomme de pin, sans pendre ni pencher de côté ni d’autre, vient de la propre sorte de nos artichauts ».

Vous remarquez que Jean de Léry, dont on a pu dire qu’il était le premier des ethnologues, a retenu le nom donné par les « sauvages », et c’est ce nom qui va être repris par la science et par la plupart des langues comme le lao, le cambodgien ou le français; d’autres comme l’anglais ou l’espagnol verront dans ce fruit surtout une ressemblance avec la pomme de pin; nous n’avons pas su déchiffrer le sens du nom thaï sapparot, mais, grâce à Jacques Lemoine, nous savons que le nom hmong tsiv puv luj, est un emprunt à la langue chinoise et non à la langue thaï comme certains le pensent.

L’ananas appartient à la famille des Broméliacées (de Bromel médecin suédois du XVII°) qui est constituée de plantes presque toutes épiphytes et presque toutes américaines. Cependant mak nat n’est pas épiphyte: c’est une espèce terrestre de plante herbacée pouvant atteindre 1m à 1,50m avec de longues feuilles lancéolées de 50cm à 1,80m, dentées en général, mais parfois lisses. La floraison de l’ananas est caractéristique des Broméliacées, avec au bout d’une tige généralement unique une couronne de feuilles courtes au-dessus d’un ensemble de petites fleurs donnant de nombreux fruits coniques, qui grossissent individuellement jusqu’à se rejoindre, formant à maturité le gros « fruit » que nous connaissons. L’écorce composée de motifs hexagonaux et la chair très juteuse sont de couleurs variables selon les cultivars.

L’ananas a été introduit en 1518 par les Portugais en Inde, il s’est ensuite répandu en Asie où chaque région a depuis longtemps développé des usages particuliers de cette plante. Au Laos les utilisations traditionnelles de mak nat sont nombreuses. Le fruit est bien entendu consommé frais, mais il est aussi l’ingrédient de certains plats cuisinés: encore vert on le met dans les soupes que l’on veut acidifier, plus mûr il est la note sucrée des nombreuses préparations dites « sucrées-salées »; les jeunes pousses sont mises dans les curry à la manière des pousses de bambou; les écorces du fruit sont ajoutées au padèk pour hâter sa fermentation et pour lui donner plus de goût. Autrefois on extrayait des feuilles un fil servant à coudre, mais c’était au détriment du fruit. Les usages médicinaux de mak nat touchent surtout les problèmes digestifs, car c’est un diurétique confirmé par les analyses chimiques; il a aussi la réputation d’être antifébrile et même abortif (feuilles, fruits verts).

S’il a été introduit depuis très longtemps dans les jardins, l’ananas est depuis peu exploité de façon extensive au Laos pour être vendu aux industries agro-alimentaires, pharmaceutiques et cosmétologiques (l’ananas ferait maigrir !). On connaît bien ici les jus et les confitures d’ananas qui entrent dans le circuit du commerce équitable. Avec une production de 32 000 tonnes par an ce fruit permet à de nombreux petits agriculteurs d’améliorer leur niveau de vie en leur procurant un emploi et un revenu fixe.

We will not teach anyone what a pineapple is, but it is interesting to say a few words about this fruit that seems so familiar that we no longer see its strange appearance. Indeed, when the first Europeans discovered it in Brazil in the 16th century, they had a lot of trouble describing it. Here is the “sketch” that Jean de Léry made in 1578, with reference to the plants of the “old continent”: “The plant that produces the fruit named by the savages Nanas is similar in shape to gladioli and still having the leaves a little curved and fluted so much around, more approaching those of aloe. It also grows not only clustered like a large thistle, but also its fruit which is the size of a medium-sized melon and shaped like a pine cone, without hanging or leaning to one side or the other, comes from the same kind of our artichokes.”

You notice that Jean de Léry, who could be said to be the first of the ethnologists, retained the name given by the “savages”, and it is this name which will be taken over by science and by most languages such as Lao, Cambodian or French; Others like English or Spanish will see in this fruit a resemblance to the pine cone; we have not been able to decipher the meaning of the Thai name sapparot, but, thanks to Jacques Lemoine, we know that the name Hmong tsiv puv luj, is a loan from the Chinese language and not from the Thai language as some people think.

The pineapple belongs to the Bromeliaceae family (from Bromel, a Swedish physician of the 17th century) which is made up of plants that are almost all epiphytes and almost all American. However, mak nat is not epiphytic: it is a terrestrial species of herbaceous plant which can reach 1m to 1,50m with long lanceolate leaves from 50cm to 1,80m, toothed in general, but sometimes smooth. The flowering of the pineapple is characteristic of the Bromeliaceae, with at the end of a generally single stem a crown of short leaves above a set of small flowers giving numerous conical fruits, which grow individually until they join, forming at maturity the large “fruit” that we know. The rind is composed of hexagonal patterns and the flesh is very juicy and varies in color depending on the cultivar.

The pineapple was introduced in 1518 by the Portuguese in India, it then spread in Asia where each region has long developed particular uses of this plant. In Laos the traditional uses of mak nat are numerous. The fruit is of course eaten fresh, but it is also the ingredient of some cooked dishes: while still green, it is used in soups to make them more acidic; when ripe, it is the sweet note in many “sweet and sour” preparations; the young shoots are used in curries in the manner of bamboo shoots; the peels of the fruit are added to padèk to hasten its fermentation and to give it more flavor. In the past, a thread for sewing was extracted from the leaves, but this was at the expense of the fruit. The medicinal uses of mak nat are mainly for digestive problems, as it is a diuretic confirmed by chemical analysis; it also has the reputation of being antifebrile and even abortifacient (leaves, green fruits).

Although it has been introduced for a very long time in gardens, pineapple has recently been extensively exploited in Laos to be sold to the food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries (pineapple would make you lose weight!). Pineapple juice and jams are well known here and are part of the fair trade circuit. With a production of 32 000 tons per year, this fruit allows many small farmers to improve their standard of living by providing them with a job and a fixed income.

Nous n’apprendrons à personne ce qu’est un ananas, il est cependant intéressant de dire quelques mots de ce fruit qui nous parait familier au point que l’on n’en voit plus l’aspect étrange. En effet, lorsque les premiers Européens l’ont découvert au Brésil au XVI° siècle, ils ont eu beaucoup de difficultés à le décrire. Voici le « portrait-robot » qu’en fait Jean de Léry en 1578, par référence aux plantes du « vieux continent »: « La plante qui produit le fruit nommé par les sauvages nanas est de figure semblable aux glaïeuls et encore ayant les feuilles un peu courbées et cannelées tant à l’entour, plus approchantes de celles d’aloès. Elle croît aussi non seulement amoncelée comme un grand chardon, mais aussi son fruit qui est de la grosseur d’un moyen melon et de façon comme une pomme de pin, sans pendre ni pencher de côté ni d’autre, vient de la propre sorte de nos artichauts ».

Vous remarquez que Jean de Léry, dont on a pu dire qu’il était le premier des ethnologues, a retenu le nom donné par les « sauvages », et c’est ce nom qui va être repris par la science et par la plupart des langues comme le lao, le cambodgien ou le français; d’autres comme l’anglais ou l’espagnol verront dans ce fruit surtout une ressemblance avec la pomme de pin; nous n’avons pas su déchiffrer le sens du nom thaï sapparot, mais, grâce à Jacques Lemoine, nous savons que le nom hmong tsiv puv luj, est un emprunt à la langue chinoise et non à la langue thaï comme certains le pensent.

L’ananas appartient à la famille des Broméliacées (de Bromel médecin suédois du XVII°) qui est constituée de plantes presque toutes épiphytes et presque toutes américaines. Cependant mak nat n’est pas épiphyte: c’est une espèce terrestre de plante herbacée pouvant atteindre 1m à 1,50m avec de longues feuilles lancéolées de 50cm à 1,80m, dentées en général, mais parfois lisses. La floraison de l’ananas est caractéristique des Broméliacées, avec au bout d’une tige généralement unique une couronne de feuilles courtes au-dessus d’un ensemble de petites fleurs donnant de nombreux fruits coniques, qui grossissent individuellement jusqu’à se rejoindre, formant à maturité le gros « fruit » que nous connaissons. L’écorce composée de motifs hexagonaux et la chair très juteuse sont de couleurs variables selon les cultivars.

L’ananas a été introduit en 1518 par les Portugais en Inde, il s’est ensuite répandu en Asie où chaque région a depuis longtemps développé des usages particuliers de cette plante. Au Laos les utilisations traditionnelles de mak nat sont nombreuses. Le fruit est bien entendu consommé frais, mais il est aussi l’ingrédient de certains plats cuisinés: encore vert on le met dans les soupes que l’on veut acidifier, plus mûr il est la note sucrée des nombreuses préparations dites « sucrées-salées »; les jeunes pousses sont mises dans les curry à la manière des pousses de bambou; les écorces du fruit sont ajoutées au padèk pour hâter sa fermentation et pour lui donner plus de goût. Autrefois on extrayait des feuilles un fil servant à coudre, mais c’était au détriment du fruit. Les usages médicinaux de mak nat touchent surtout les problèmes digestifs, car c’est un diurétique confirmé par les analyses chimiques; il a aussi la réputation d’être antifébrile et même abortif (feuilles, fruits verts).

S’il a été introduit depuis très longtemps dans les jardins, l’ananas est depuis peu exploité de façon extensive au Laos pour être vendu aux industries agro-alimentaires, pharmaceutiques et cosmétologiques (l’ananas ferait maigrir !). On connaît bien ici les jus et les confitures d’ananas qui entrent dans le circuit du commerce équitable. Avec une production de 32 000 tonnes par an ce fruit permet à de nombreux petits agriculteurs d’améliorer leur niveau de vie en leur procurant un emploi et un revenu fixe.

We will not teach anyone what a pineapple is, but it is interesting to say a few words about this fruit that seems so familiar that we no longer see its strange appearance. Indeed, when the first Europeans discovered it in Brazil in the 16th century, they had a lot of trouble describing it. Here is the “sketch” that Jean de Léry made in 1578, with reference to the plants of the “old continent”: “The plant that produces the fruit named by the savages Nanas is similar in shape to gladioli and still having the leaves a little curved and fluted so much around, more approaching those of aloe. It also grows not only clustered like a large thistle, but also its fruit which is the size of a medium-sized melon and shaped like a pine cone, without hanging or leaning to one side or the other, comes from the same kind of our artichokes.”

You notice that Jean de Léry, who could be said to be the first of the ethnologists, retained the name given by the “savages”, and it is this name which will be taken over by science and by most languages such as Lao, Cambodian or French; Others like English or Spanish will see in this fruit a resemblance to the pine cone; we have not been able to decipher the meaning of the Thai name sapparot, but, thanks to Jacques Lemoine, we know that the name Hmong tsiv puv luj, is a loan from the Chinese language and not from the Thai language as some people think.

The pineapple belongs to the Bromeliaceae family (from Bromel, a Swedish physician of the 17th century) which is made up of plants that are almost all epiphytes and almost all American. However, mak nat is not epiphytic: it is a terrestrial species of herbaceous plant which can reach 1m to 1,50m with long lanceolate leaves from 50cm to 1,80m, toothed in general, but sometimes smooth. The flowering of the pineapple is characteristic of the Bromeliaceae, with at the end of a generally single stem a crown of short leaves above a set of small flowers giving numerous conical fruits, which grow individually until they join, forming at maturity the large “fruit” that we know. The rind is composed of hexagonal patterns and the flesh is very juicy and varies in color depending on the cultivar.

The pineapple was introduced in 1518 by the Portuguese in India, it then spread in Asia where each region has long developed particular uses of this plant. In Laos the traditional uses of mak nat are numerous. The fruit is of course eaten fresh, but it is also the ingredient of some cooked dishes: while still green, it is used in soups to make them more acidic; when ripe, it is the sweet note in many “sweet and sour” preparations; the young shoots are used in curries in the manner of bamboo shoots; the peels of the fruit are added to padèk to hasten its fermentation and to give it more flavor. In the past, a thread for sewing was extracted from the leaves, but this was at the expense of the fruit. The medicinal uses of mak nat are mainly for digestive problems, as it is a diuretic confirmed by chemical analysis; it also has the reputation of being antifebrile and even abortifacient (leaves, green fruits).

Although it has been introduced for a very long time in gardens, pineapple has recently been extensively exploited in Laos to be sold to the food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries (pineapple would make you lose weight!). Pineapple juice and jams are well known here and are part of the fair trade circuit. With a production of 32 000 tons per year, this fruit allows many small farmers to improve their standard of living by providing them with a job and a fixed income.

Nous n’apprendrons à personne ce qu’est un ananas, il est cependant intéressant de dire quelques mots de ce fruit qui nous parait familier au point que l’on n’en voit plus l’aspect étrange. En effet, lorsque les premiers Européens l’ont découvert au Brésil au XVI° siècle, ils ont eu beaucoup de difficultés à le décrire. Voici le « portrait-robot » qu’en fait Jean de Léry en 1578, par référence aux plantes du « vieux continent »: « La plante qui produit le fruit nommé par les sauvages nanas est de figure semblable aux glaïeuls et encore ayant les feuilles un peu courbées et cannelées tant à l’entour, plus approchantes de celles d’aloès. Elle croît aussi non seulement amoncelée comme un grand chardon, mais aussi son fruit qui est de la grosseur d’un moyen melon et de façon comme une pomme de pin, sans pendre ni pencher de côté ni d’autre, vient de la propre sorte de nos artichauts ».

Vous remarquez que Jean de Léry, dont on a pu dire qu’il était le premier des ethnologues, a retenu le nom donné par les « sauvages », et c’est ce nom qui va être repris par la science et par la plupart des langues comme le lao, le cambodgien ou le français; d’autres comme l’anglais ou l’espagnol verront dans ce fruit surtout une ressemblance avec la pomme de pin; nous n’avons pas su déchiffrer le sens du nom thaï sapparot, mais, grâce à Jacques Lemoine, nous savons que le nom hmong tsiv puv luj, est un emprunt à la langue chinoise et non à la langue thaï comme certains le pensent.

L’ananas appartient à la famille des Broméliacées (de Bromel médecin suédois du XVII°) qui est constituée de plantes presque toutes épiphytes et presque toutes américaines. Cependant mak nat n’est pas épiphyte: c’est une espèce terrestre de plante herbacée pouvant atteindre 1m à 1,50m avec de longues feuilles lancéolées de 50cm à 1,80m, dentées en général, mais parfois lisses. La floraison de l’ananas est caractéristique des Broméliacées, avec au bout d’une tige généralement unique une couronne de feuilles courtes au-dessus d’un ensemble de petites fleurs donnant de nombreux fruits coniques, qui grossissent individuellement jusqu’à se rejoindre, formant à maturité le gros « fruit » que nous connaissons. L’écorce composée de motifs hexagonaux et la chair très juteuse sont de couleurs variables selon les cultivars.

L’ananas a été introduit en 1518 par les Portugais en Inde, il s’est ensuite répandu en Asie où chaque région a depuis longtemps développé des usages particuliers de cette plante. Au Laos les utilisations traditionnelles de mak nat sont nombreuses. Le fruit est bien entendu consommé frais, mais il est aussi l’ingrédient de certains plats cuisinés: encore vert on le met dans les soupes que l’on veut acidifier, plus mûr il est la note sucrée des nombreuses préparations dites « sucrées-salées »; les jeunes pousses sont mises dans les curry à la manière des pousses de bambou; les écorces du fruit sont ajoutées au padèk pour hâter sa fermentation et pour lui donner plus de goût. Autrefois on extrayait des feuilles un fil servant à coudre, mais c’était au détriment du fruit. Les usages médicinaux de mak nat touchent surtout les problèmes digestifs, car c’est un diurétique confirmé par les analyses chimiques; il a aussi la réputation d’être antifébrile et même abortif (feuilles, fruits verts).

S’il a été introduit depuis très longtemps dans les jardins, l’ananas est depuis peu exploité de façon extensive au Laos pour être vendu aux industries agro-alimentaires, pharmaceutiques et cosmétologiques (l’ananas ferait maigrir !). On connaît bien ici les jus et les confitures d’ananas qui entrent dans le circuit du commerce équitable. Avec une production de 32 000 tonnes par an ce fruit permet à de nombreux petits agriculteurs d’améliorer leur niveau de vie en leur procurant un emploi et un revenu fixe.